A Google search of “How to Self-Publish a book” produces about 282 million results.

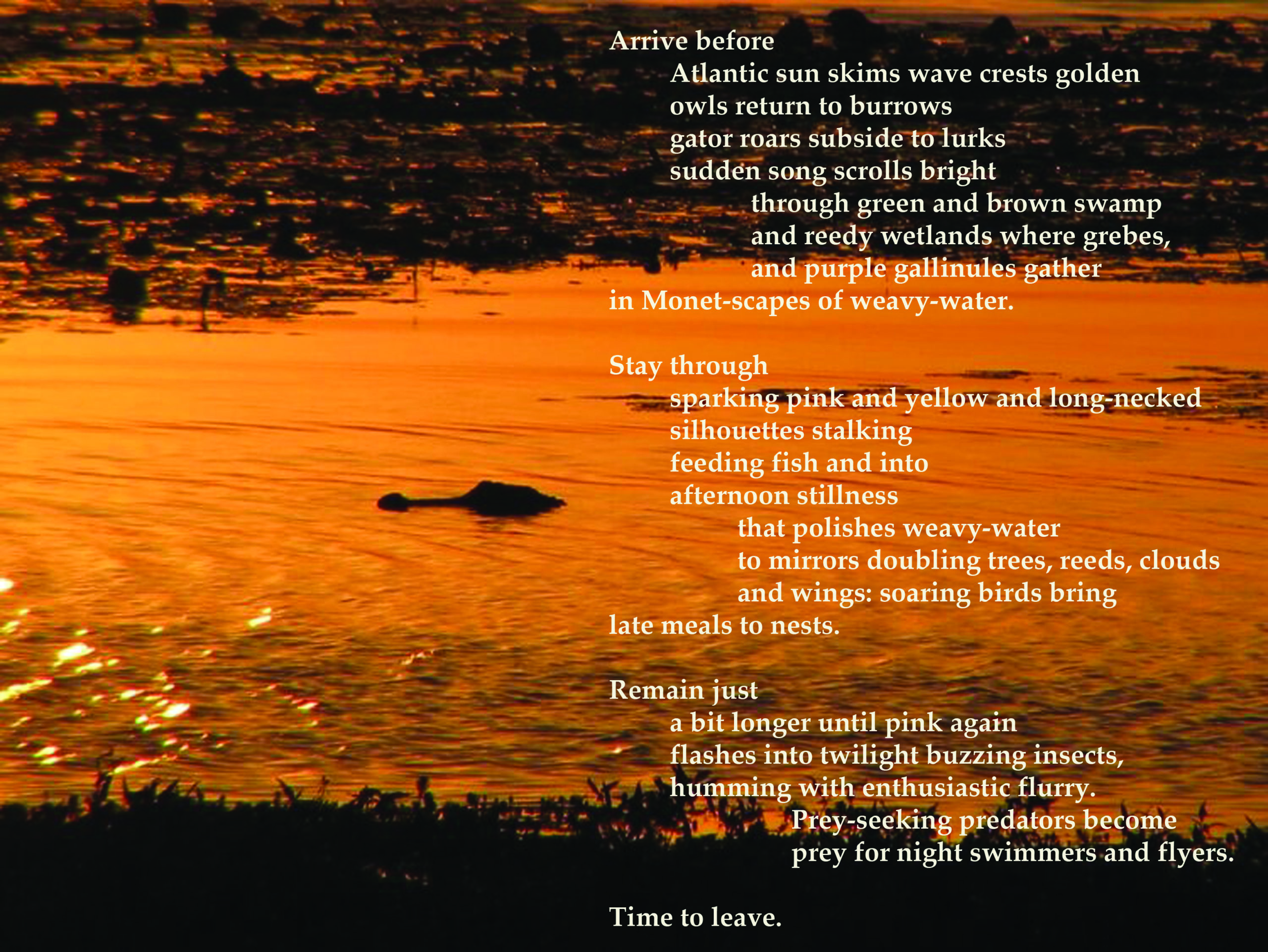

The Publishing Swamp

No, they don’t all agree. Nonetheless, the amount of information available provides a clue as to how many people are considering self-publishing. This feels a little like landing in a swamp with a large gator.

Rather than starting your search with 282 million suggestions, start with yourself. Your goals are unique. Your work is unique. Make some deep dives into a study of your writing and goals before making a publishing commitment.

As you take that dive, try to set aside any bias that has grown out of what you’ve heard about Indie or traditional publishing. Other people will have had experiences that come out of their own journeys. Yours will be unique. Start by asking yourself some specific questions.

-

Why do you want to publish and should you do so?

Personal Writing

Perhaps you write away your tensions or write in journals to create a family keepsake (such as pioneers kept when crossing the country). You might write poems or essays or even fiction, but you’re not into revision and editing. You write and then move on.

Maybe you’ve shared some of your work and have been told “Wow! This is good! You should publish.”

That doesn’t mean you should do so, particularly if the process is going to steal time and energy from the ongoing writing you love. You might consider using nice journal bindings or even scrapbooks. Let your creativity sparkle. If you do a book, you might want one or two copies from an organization like Shutterfly with a mix of your pictures.

Specific Audience

On the other hand, maybe you want a more traditional book for a specific audience. Perhaps some relatives are having a golden wedding anniversary, and you’ve penned some family stories, poems, or essays that will help celebrate that event.

A specific audience might be slightly broader but not on a commercial scale. For instance, a local environmental organization in my region has talked to me about reprinting its guidebook for water access in our county. Tourists and residents find the book useful to find small coves, hidden beaches, and small parks that are public. It’s unlikely anyone other than this audience will be interested in the book even though it includes some good environmental information. A commercial, traditional publishing house wouldn’t be interested. Self-publishing is the way to go.

Family histories, biographies of little-known individuals, memoirs of military experiences: many books fall into this category. Rarely will traditional publishers be interested unless the person’s story is of national interest such as Margarethe Cammermeyer’s book, the second edition of which I edited for her, Serving in Silence. Her work changed military policy and was made into a movie, which moved it into a larger audience.

Sharing

You enjoy writing and you want to share what you’ve written with as many people as possible. Your work may not win a Pulitzer, but you hope it will bring pleasure or instruction to anyone who picks up the book. Having the book “out there” is all you want. Again, trying to market to traditional publishers will likely drown your enthusiasm.

My books How Many Words for Rain and Interpretative Guide to Western Northwest Weather Forecasts are examples of “gift” books or specialized books. The first, a mix of photos and poems on rain, was actually accepted by a university press just before the press closed. The second one has done quite well as a humor/gift book but no press would have wanted to risk it, especially for expensive color printing that was essential for the photos to come across well.

Professional writer

You think your work will interest a broad audience. You have confidence in your writing and public response. You want to be able to do readings, appear at conferences, get reviews, maybe win prizes. Trying the commercial publishers and small presses first might be the best way to go. Indie books can and have done all that, but because of negative attitudes in the industry toward self-publishing, reaching your goals will be more difficult.

-

What skills/resources do you possess to produce the book?

Throughout much of the 1900s, writers focused on their craft. Publishers had readers, editors, copyeditors. In-house production included designers for the book and cover. The publishers took care of distribution and marketing.

As computers became the norm, many publishers cut back on their services. Writers today are expected to turn in manuscripts that have been edited and proofed (unless the writers have a proven track record). Book production is like a self-checkout line unless you’re a guaranteed best seller. Nonetheless, the publisher carries the financial load and a significant part of the process.

If you go Indie, you become the publisher.

Basic requirements

Your manuscript will require revision, editing, and proofing. Few writers are good editors of their own work. Editing one’s own work parallels Abraham Lincoln’s comment that any lawyer representing herself has a fool for a client. That doesn’t mean you can’t do it, but you need to be skilled.

All good editors aren’t housed in publishing houses. Are you part of a writing group who will help with critique and proofing? Or do you have the available funds to hire an editor, consultant, or proofreader?

If you opt to hire someone, plenty of professional services are available. Do your homework, and make sure that you’re trusting reliable people and that you’re not over-paying. You can find a list of standard rates at Editorial Freelancers Association. The Literary Marketplace, available at most libraries (it’s expensive) also has extensive listings of all sorts of literary services, including agents and publishers.

Some printers, such as BookBaby also offer such services. They’ll work with your manuscript through design and printing. Again, do your research. Some are very expensive and might not produce the results you’d like.

The finishing touches

Once the manuscript is ready, the book has to be designed. This includes title choice, basic interior layout, and cover design. Do you have the skills?

Again, you can find millions of Internet sites about book design but, again, they don’t all agree and some suggestions might not apply to your book. If you go with an all-in-one service such as BookBaby, you won’t need to search for a designer.

When working with designers, you’ll walk a fine line between your own interests and the more commercial look most designers suggest. For instance, my last book Quantum Consequences, doesn’t have a cover that “looks like all the other books in its genre,” a recommendation by one design site. However, I had my own reasons for using that cover. Period.

Again, your goals determine your choices. And you can always pursue self-publishing options while you submit your book to agents and publishers: you’ll have plenty of time.

Budget

Realistically your cost for self-publishing might be higher than any return you’ll receive from the book, especially if you’re hiring professionals for the final stages. Plan your budget based on what you can afford before publication, not after. Stick to the budget. Turning the book into a huge debt takes all the pleasure out of your success.

Of course, if you go the traditional route, the idea is that the publisher thinks your book will make enough money to pay for costs and provide a profit. For them. You might never receive more than a small advance. Small, nonprofit presses might think the possibility for profit is slight, but they rely on funding from universities and/or donations, and they want good books to build up their reputations and donor lists, not their coffers. Authors often receive only copies as payment, however. Be prepared to spend time in lieu of money; the traditional route allows travel at the speed of a slug on sleeping pills.

-

Understand distribution.

Even if you decide to go with a publisher, make sure you understand the distribution agreement. Some small publishers offer books only on their Websites. Others use SPD (small press distribution). Large publishers might agree to national distribution but only to those stores that order a certain quantity and with a limited shelf life (maybe only ten days). If enough haven’t sold within that time, you could find your book remaindered before it’s been out a month.

If you self-publish, where your POD/digital book is set up will determine where the book is available. If, for instance, you go with Kindle Publishing, wholesalers can’t order your book. You’ll have to go to bookstores and sell the book yourself.

Other POD companies have broader distribution. For instance, IngramSpark has a large distribution system and within days after your book (print and/or digital) is uploaded, it will be available to wholesalers around the world. You’ll see it placed on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and even Wal-Mart. Your local bookstores can order the book on their own computers.

The question of where you want the book to be available is tied to why (see #1) you want to publish.

-

Marketing

If you want your book to be noticed, you’re going to have to shoulder marketing responsibility whether you choose Indie or a large publisher. Often called “building a platform,” this includes social media, maintaining a Website and blog, making personal appearances, e-mailing friends/family, submitting press releases…the extensive process steals time from writing.

Don’t get frustrated!

To cut down on the post-publication frustration, limit the time you spend on marketing. Plan your activities to get the most out of each minute you spend. You can find a lot of information online under 5-minute book marketing tips.

Again, you can hire a professional, a publicist. Make sure you’ve done your research to find someone who is respected and affordable. Poets & Writers has an interesting article on this.

5. Know the History

Once you know your own goals, understanding publishing history will help you understand the processes. Most people know that printing presses and publishers have been around for centuries. Not everyone knows that self-publishing also has a long history (the Internet didn’t birth the idea) with many famous authors. Edgar Allen Poe and Charles Dickens as well as Walt Whitman join contemporary writers John Grisham and Beatrix Potter as self-published authors. See Poets & Writers for a timeline.

Nonetheless, the advent of computerized POD in the 1980s was the start of serious negativity toward self-publishing. The stigma’s heart beats to the drum that the best product comes from a large company, that a self-published book is inferior to those that make their way through the mazes of large houses or small presses.

Some of that bias is justified.

The 1980s birth of POD companies offered few choices. Marketing options were scanty, expenses were high (in time if not money), and the results were unpredictable. Self-published books tended to look self-published: poor paper quality, odd sizes, print variances, uneven pages, etc. Poetry usually was scrambled.

The industry has improved, at least in regard to looks and publishing quality. In fact, many large publishing companies rely on POD or digital resources these days after that first rush following the release date. However, some wholesale buyers still check stocks (trying to weed out Indie books) because returning POD books can be an issue. Indie publishers must consider allowing returns of books to offset that concern.

Another problem with the initial stages of self-publishing in the late 1900s was that everyone could and did publish anything. The only limitation was financial. A flood of books that needed revision, editing, and proofing dampened reader enthusiasm, turned off reviewers, and frustrated wholesalers.

Keep in mind that commercial book quality also varies from publisher to publisher. Some big houses turn out cheap looking books that sell cheaply. Also, reviewers’ negativity extends to the writing now and then. Just because something comes from a big press and is written by a famous person doesn’t protect the work from reviewers. An example comes from the The New York Times about Sleeping Beauties by Stephen King and Owen King:

What you may well come away thinking is: meh. For a book about resetting gender stereotypes, this one clings surprisingly tightly to them.

That best seller, released by Scribner, was obviously not injured by negative reviews. The key to that paradox is our love of branding/love of the popular. Many people would buy a Stephen King book even if they first had to slay dragons.

Our belief in branding, again, is one reason we don’t trust the “anyone can self-publish” concept. Children make out specific Christmas lists (no surprises, please) and people get mugged for particular shoes. I knew a kid who was bullied in school because he wore K-mart clothes.

Consider how we brand authors, expecting them to stick to one genre, even one character. One of my friends who writes for a major publishing house had to start using a pen name when she wanted to write a different genre. Striking out on your own is challenging (even frightening) in our cliquish society.

Because of all of this, if you go Indie, expect to be marginalized. This applies to anything you do, not just books. For instance, Stagecoach Mary Fields was the only woman allowed in saloons in Montana in the late 1800s, but she wasn’t welcome at church socials.

So if your Indie books are apt to be marginalized–shunted aside by book stores, libraries, and readers–why bother? As mentioned above, a lot of that depends on your goals.

In addition to the reasons mentioned earlier, some of us are worn out on the pitching, wooing, and begging that often goes along with submissions, query letters, and maneuvering through the conference and workshop networking.

Forty years ago, the process felt a little more like professional networking. Over time, as publishing companies continued to merge and gobble up smaller companies, the ability to be unique, an individual, in the publishing world lessened. Respect for authors dwindled. These days, months can pass with no word back from agents/editors; in fact, some never reply at all.

Even if a book is accepted, the results could be disappointing. If the book is low on the publisher’s list, even placement in bookstores can be a problem. You won’t find your book in the window. Some books never make it to market even after being accepted.

Disappointments don’t happen to only “bad writers.” John Gardner wrote for 15 years before The Resurrection was published.

I was furious. You know, I’d read novels by people I thought were awful compared to me. And I’d read my rejection slips. . . . But I was stubborn. And I covered myself. I became a medievalist. I wrote many articles and translations so that I knew I’d be safe all my life, and then I wrote [fiction]. If people asked me what I was I’d say ‘I’m a writer,’ because the next question was ‘What have you published?’ And I’d be embarrassed. . . . by Louise Sweeney, interview June 26, 1980 The Christian Science Monitor

No Easy Answer

To succeed with an Indie or traditionally published book, you’ll need tenacity and patience. For an Indie book you’ll also need to either study your craft intently or pay for experts who can help with the editing, proofing, designing and maybe even the marketing. In my opinion, learning ever more about writing and publishing will benefit all writers no matter which route they choose; you can’t lose by knowing your craft.

Before I reached the decision to go Indie from now on, I had forty years of publishing, editing, and teaching writing to back me up. My work was included in many books from different presses. Although I was still marketing to magazines for short work, I no longer had patience for spending years running in a hamster wheel to get a book read and accepted. Sometimes marketing a book takes longer than writing one. I’d done that with earlier novels that now sit in boxes (maybe I’ll resurrect them).

Acceptances were often worse than rejection. I’d had books accepted by both agents and publishers only to have train wrecks: the agents couldn’t sell the book in their allotted time; one publisher accepted one of my books then backed out because his partner didn’t like the book; in another case, the publisher who accepted a book went out of business before the book was printed. Bah! Humbug!

Find your own path!

Now, as a practicing curmudgeon, I’m most interested in doing what I want to do. I’ll switch genres. I’ll set up covers or designs for personal reasons that don’t fit with current marketing trends. “Indie” stands for independent: don’t let the industry creep in and convince you that what you want to do is “wrong.” I’m independent in every sense and loving it.

In other words, I’m having fun writing again, a quality that too often has become lost in the “industry.”

Having fun is perhaps one of the best reasons to self-publish. Enjoy it!

Compiling your short stories, poems, or essays into a compelling book collection involves alchemy.

Compiling your short stories, poems, or essays into a compelling book collection involves alchemy.