You can’t escape the web of life

Maintaining and protecting your web results in a bounty for all. Photo by Cherie Ude. Previously published in Interpretative Guide to Western Northwest Weather Forecasts.

(See Natural Resources, the environment and eco-systems)

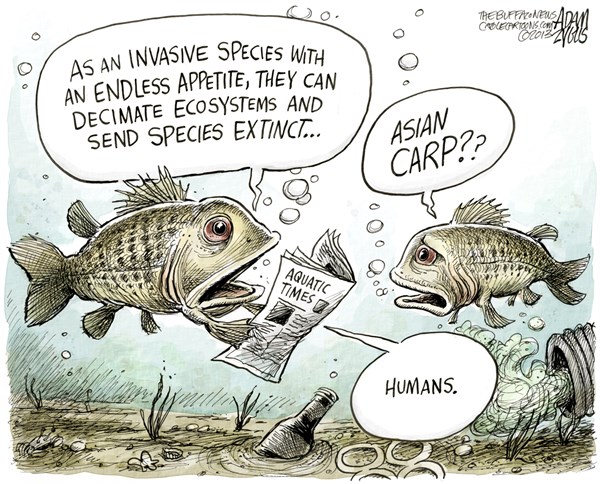

If you could separate yourself, you’d destroy your connections to life itself. The Web of Life confirms that, contrary to what we might think, humans are not self-sufficient.

For instance, if you eat, you’re dependent on microbes that maintain soil health. You’re dependent on insects that pollinate crops. These microbes and insects are dependent on clean water and soil.

In other words, if you want breakfast, you need a healthy habitat. Such an environment is good for crops and one in which birds, lizards, and amphibians thrive. These, in turn, help manage insects (both those that pollinate and those that don’t). The entire system maintains clean water and air.

Food Chain or Web of Life?

Perhaps you think of this as the “food chain,” but that is limited and no longer useful for understanding our connections and dependency on the environment. A food chain refers to who eats whom in the wild. A web illustrates where all creatures find what they need to survive in order to be part of that food chain (Food chains & food webs).

Humans have sometimes tried to manage without considering the Web of Life. For instance, in the past, some farmers tried raising crops by plowing without regard to soil damage and by saturating the water, plants, and soil with poisons to kill insects. In turn, they’ve harvested dust bowls, abiotic crop diseases, and residual poisons that have negative effects on people and animals through contaminated food and water. WWF–Sustainable Agriculture

Who Needs Plants?

Perhaps you think you’d get along fine without plants. However, if you eat animals, those animals depend on plants for food. Even wild carnivores, such as lions, get their meat from herds of animals that graze on plants.

So if you eat, you depend on biodiversity and a healthy environment.

In other words, biodiversity is crucial to successful life on Earth. Humans can’t, on their own, create conditions to raise enough plants to feed all the animals and people on Earth. Each living thing has a role in sustaining life. The more this is maintained, the more you’ll have to eat. This is the web of life.

Breathe a Little Light

The sun brings power to plants. Plants pass that power on to all life. Photo by Marian Blue

Taking a step back, plants need more than water. They need the power of sunlight for their complicated process of photosynthesis (6CO2 + 6H2O + Light energy → C6H12O6 (sugar) + 6O2) (Smithsonian Science Education Center-What is Photosynthesis?). In this process, plants breathe, and what they exhale is the oxygen you need to inhale.

If something interferes with the balance and quality of sunlight, the entire system begins to fall apart. That’s why horrible clouds of pollution can kill people (Great Smog of London–Britannica).

Every breath you take is thanks to plants.

So your very life itself–breath, water and nutrition–depends plants.

You depend on an environment in which plants can remain healthy. This is the Web of Life.

Habitat, Ecosystem, & Biomes

You’ll often hear people refer to environment, ecosystem, habitats, and biomes as though the terms are interchangeable. They aren’t. (Wilderness Classroom–Understanding Habitats, Ecosystems and Biomes)

Habitat

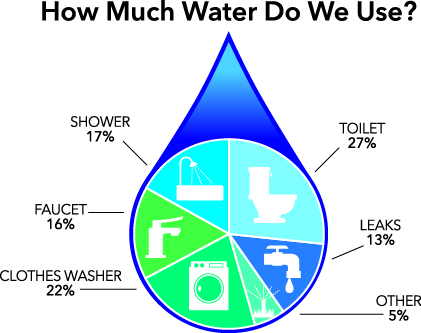

A habitat is where something is native, where it can grow and thrive naturally without over-populating the area. Habitat consists of what you need in the way of food, temperature, humidity, and space. In one sense, your home is your habitat (where you can find food, water, safety, and shelter). (For more on conserving water, see Share the Joys of Water )

Ecosystem

An ecosystem is the neighborhood, functioning as a whole. In one sense, your habitat is sustained by connections to water and sewer systems, by trash collectors, by power lines, and more. In the wild, an ecosystem is sustained by water and food supplies. Often these are maintained through plants, both as food and filters to maintain fresh water. Those things encourage animals to move in. In turn, predators move in.

Biome

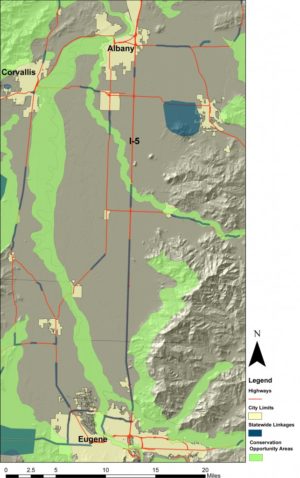

A Biome is a large geographical area. I live in the Pacific Northwest which is a moist temperate coniferous forest biome. It includes some high and low elevations (sea level to 14,000 feet). We have beaches, lakes, and rivers along with a number of different ecosystems for each. Habitats support everything from vast fungi networks to grizzly bears and cougars.

Pacific Northwest Biome

Many kinds of fungi love snags. Critters love fungi. Photo from Interpretative Guide to Western Northwest Weather Forecasts.

The Web of Life in the Pacific Northwest depends on basic plants and fungi. Fungi operate largely unseen, but they play a major role in breaking down organic material in the forest, which, in turn, provides nutrients for growing things.

Many creatures eat fungi as well. Plants, from tiny mosses to giant old growth trees, are all part of the underground root system that provides healthy habitat for microbes, bugs, arachnids, slugs and more. These, in turn, provide a smorgasbord for frogs, salamanders, lizards, snakes, and birds.

This is also excellent habitat for small mammals such as squirrels that thrive on tree cones. Here, too, you find raccoons that enjoy meals of small mammals and fish and other water-bound life on beaches. Beavers build dams and create small lakes that provide bountiful habitat for fish and birds. Salmon that come to spawn provide meals for bears, otters, and eagles. Salmon spawning, in turn, is vital to a host of whales, dolphins, otters and more that live in the ocean biome west of the Pacific Northwest.

This extensive biome Web of Life thrives, as always, from plants. For more, check out Web of Life–Nature North West.

Another Web of Your Life

During Covid, many people discovered how important their social webs are. They depend on other people for recreation, social networks, income, package delivery, manufacturing (clothes, kitchen appliances, cars and more), growing food…the list is extensive. What we sometimes forget is that, in the Web of Life, connections only to people will eventually lead to a dead end.

Everything is connected. We need to protect all the biodiversity and health on our planet, which includes ourselves, our families, our friends, and even things we can’t see.

Protect and maintain your Web of Life for yourself, your family, your Earth. (6 Ways to Preserve Biodiversity)

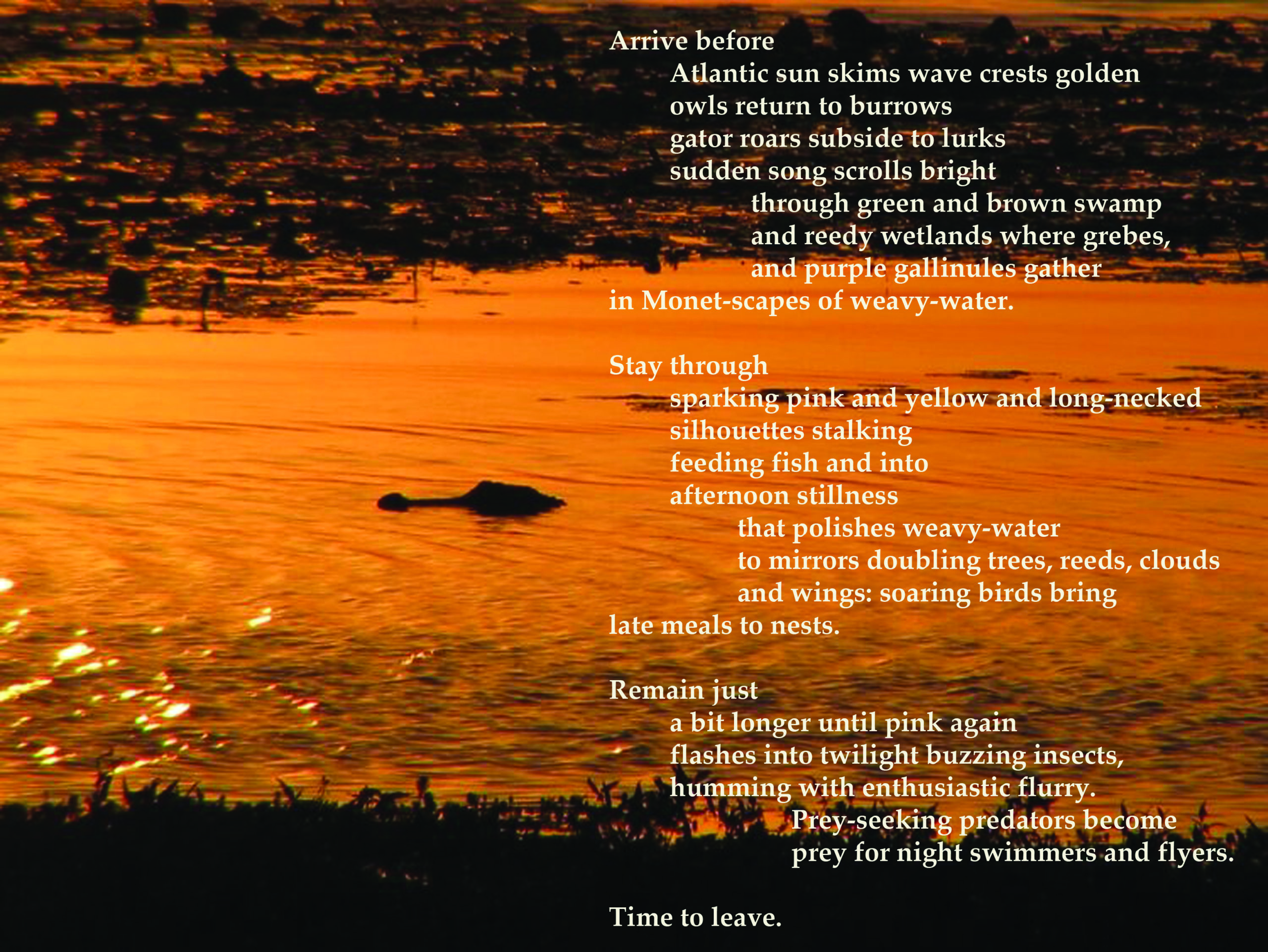

Marian Blue is pleased to announce her publication of her prose poem, “Wild Spaces Without and Within” in the current issue (Spring/Autumn 2021) of Snowy Egret. This outstanding magazine celebrates the “abundance and beauty of nature and examine(s) the variety of ways, both positive and negative, through which human beings interact with the landscape and living things.” It’s an honor to have material included.

Compiling your short stories, poems, or essays into a compelling book collection involves alchemy.

Compiling your short stories, poems, or essays into a compelling book collection involves alchemy.