Oh, No! Not Marketing!

Every writer–every artist in every field–whom I’ve met dislikes marketing, yet the modern world thrives on marketing. Of course, it thrives on creating art, too, and countless books, classes, and conferences have material telling you how to get words on the page and complete work.

Unfortunately, less is available on marketing. The problem, of course, is that without marketing, your work can wind up packed away on thumb drives and backup drives forever. You can avoid this with a few simple good marketing habits.

- Identify your goals. This is the big picture.

Not every artist has visions of The New York Review of Books in mind for his/her best-selling books. Some do. Some want to self-publish and some don’t want to publish at all. Your goal will determine where, when, and how you market your material and yourself.

For instance, you may want to write poems for friends or family or write a family biography or short blurbs to go with photos. You want to write well, and what you have to say is important, but marketing doesn’t play into the writing, the results, or the satisfaction. Your choice will be whether to do a photo book or maybe a small book with a limited number of copies. Many companies do this, such as Blurb, Shutterfly, and many others.

If your goal is to self-publish to a larger market–that is, you do want to get your work out there and read–don’t assume you can skip marketing. People who self-publish work hard (and daily) to put their work where readers can find it. Plan on building up a Web presence (everything from social media to an author Web page). Look up the Web presence of other authors for ideas.

You’ll be contacting bookstores, conferences, and workshops with ideas for classes or readings, talks, and classes. Have a professional business card. Make up posters to leave with bookstores. Have a blog and send out emails to subscribers. Write reviews and post material on other authors’ pages. In other words, daily get your name printed somewhere. This is also true if you go through a small press. Set this in motion as you write; don’t wait until you publish (that’s too late)!

If you publish through any traditional channels, you’ll find that publishers will expect you to build up your Web presence and promote yourself, too (you’ll hear the word platform, which is described in the previous paragraph). However, you’ll probably have some guidance and help along the way if you’re with a larger press.

The first step to having that large publisher, of course, will be to have your work accepted, and to do that, you have to continually submit.

- Schedule marketing daily.

Tomorrow is only a way to procrastinate.

While marketing isn’t something you need to obsess over as most of us do over our writing, it’s important to do daily for the simple reason that if you don’t, you’ll look at your marketing journal one day and discover that it’s been a month and you’ve done nothing; that you don’t have anything actively making the rounds of editors; that you just don’t have the energy to “start over again.”

In addition, the more material you have “out there,” the less you’ll be concerned about each submission.

As with writing, I recommend that you set both a minimum and a maximum time to spend marketing every day. The reason for both is simple: you need to trick yourself into avoiding procrastination techniques. If you don’t limit your time and you’re having a good day, you may spend the entire day working on marketing. Then you’ll use that as an excuse to not market the next day–or for the next week.

This time should be spent reading publications, prowling the Internet for publications (don’t forget libraries), and checking out various directories of publications (such as CLMP’s Literary Press & Magazine Directory, and Poets & Writers databases of magazines, presses, agents, etc.).

Each day send out at least one submission.

Rationalization and procrastination are best buds.

- Keep a list of likely publications, presses, agents for your work.

To avoid endlessly searching through lists of calls for submissions, create your personalized list. Include only publications that use material similar in nature to what you write. For instance, if you write mostly dramatic monologues on love, don’t bother to include publications that want only cyberpunk poems.

Part of this list creation requires that you research publications. Make sure they are places where you want your work to appear. Make sure that you’re not signing away all rights and know what your rights are. Decide whether you want to publish online only or if you want to focus on print publications.

Of course, in order to make this list, you have to know what editors are publishing. This means you have to read: publications, submission guidelines, and magazine listings.

Writers too often skip reading publications. Excuses abound: there are too many! they cost too much! I don’t have time!

Protestation is a cousin to procrastination and rationalization.

In short, if you don’t read publications, you will find that you irritate editors who receive work inappropriate for their publication; also, you will be guaranteeing that you’ll receive more rejections than acceptances; finally, you will spend more on wasted submission cost (reading fees and entry fees, for instance) and wasted time. This is a lose/lose situation.

Not reading publications is akin to a nurse who administers medication without bothering to read the patient’s chart.

Even if you can’t afford to buy a copy of every magazine being published today (who can?), almost every magazine has a website offering story samples to read for free. If the stories that the publication editor has chosen for examples are histrionics laced with characters who can’t speak coherently and who are riddled with drugs, sex, and violence, then that is what the editors want. I’m not saying the stories aren’t good or that they don’t depict an aspect of our society, but an editor isn’t going to suddenly switch from dramatic, teen drug culture to a deep character study about a woman in her 40s who can’t find work.

A good way to gain access to more magazines is to form a group of friends to share efforts. Each person can subscribe to or buy one issue of a magazine; swap them among yourselves. More on group marketing below.

Don’t forget about anthologies. These often provide more diverse opportunities than you’ll find in literary/small press magazines.

Anthologies may be based on a theme or a region or a topic. You can find many of these simply by using your search engine to look up “anthology submissions” or, to be more specific “fiction anthology submissions.” Beware of anthologies that include all submissions if writers buy the book or pay a fee (do your research); such publication is almost like not publishing at all.

Another way to find markets is to read the Best of …; these are anthologies that include stories from a diverse range of literary magazines. Libraries usually include, for instance, The Best American Short Stories. You don’t need to spend a fortune on your reading regime and you’ll learn a lot about what different magazines like.

Ultimately this will save you time, effort, and frustration.

- Don’t cross anything off your list too quickly.

Don’t be too quick to skip a publication just because the description has a word or two that you think can’t possibly apply to you (i.e., your personal bias). For instance, the annual calls for submission to Orison Books uses the term “spiritual” often, but the publication is not limiting itself to organized religion or even religion at all. Read deeper to find out what the editors do mean and whether you might not be writing something that fits the editor’s interest (such as material that illustrates the mystery underlying characters’ actions and goals–their spiritual natures–or magical realism). Research is careful and detailed examination, not skimming.

Finally, don’t cross magazines off your list because their prestige intimidates you. For instance, your work may be right for The New Yorker; if so, submit there. Don’t decide not to do so just because you don’t have a “name.” On the other hand, don’t submit to prestigious magazines just because they are prestigious. Submit only if they fit your work.

- Pay attention to the editors and staff on publications that seem right for your list.

If the publication has material you enjoy reading and that is similar in message, tone, genre, etc. to what you’re writing, learn more about the editor and staff’s writing, particularly where it has been published. Those publications may also like your work. Then you look up those publications and get the names of that editor and staff, and so forth. If you keep following this trail, you’ll get some repetitions, but you’ll also add to your list of publications (magazines and anthologies) that are likely to accept your work.

- Form good social connections.

Writers usually need alone time for creation, but no writer can market today without creating social links. Create your author’s Web page, your Facebook page, your Linkedin profile, your Twitter account, and your Wiki page and update them frequently. This is related to platform building above.

Also, attend readings, conferences, and other events to support other writers. Find out how you can be included in future activities. Have a professional business card to hand out. If you have books, always have a few copies with you.

Do not carry around manuscripts to drop on agents or editors!

This is unprofessional and although you will be remembered (and discussed), the reasons for such discussions won’t be helpful to your career.

- Keep a meticulous journal.

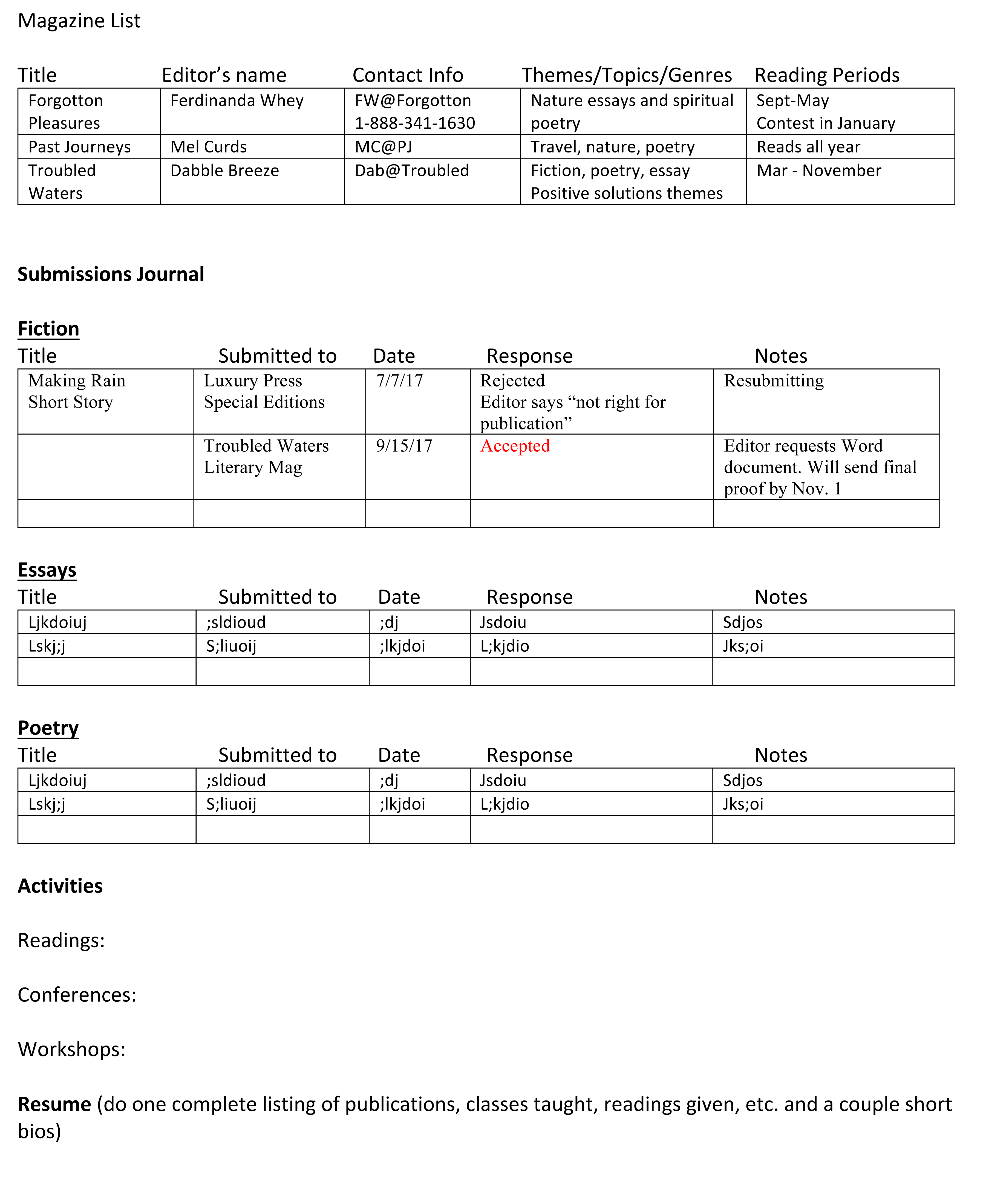

Include the list of likely markets, your submissions (including the results and dates), your activities, and your writing credentials. Many people keep this online and many prefer a hard copy journal. For those of us who expect the worst, keep a hard copy even if you prefer online.

As part of this journal, keep your list of credentials (resume), publications, readings, and online links up to date. You may think that, as a writer, you won’t need a resume, but if you’re going to apply for workshops or grants, you’ll be glad to have the resume handy.

Interestingly, I’ve had to refer back to these journals often. Don’t erase or throw them away! See sample below.

***

Ultimately, if you write and market every day, you’ll find that your publication success increases steadily. Then when you hear other writers bemoaning the number of rejections they receive for every publication, you can advise them on the best way to market.

Marketing Journal