Invaders!

Invasive species threaten habitat and human health.

Whose fault is it? Who can fix the problem?

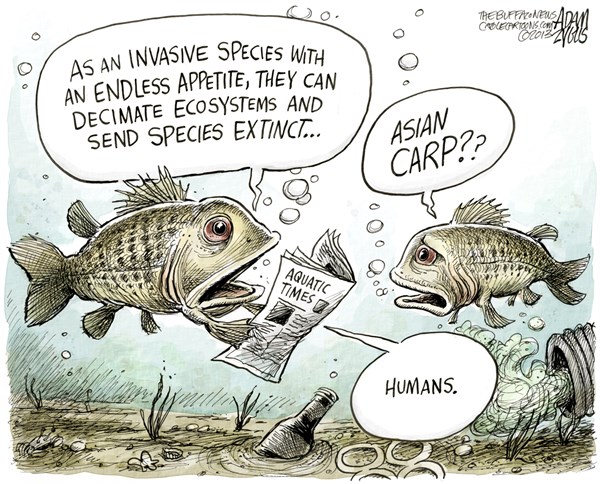

The word itself–”invasive”–blames unwanted behavior on the invaders themselves. Vikings storming through Britain; Imperialists denying the rights of native citizens; Nazis invading, well, almost everyone: these suggest willful and aggressive purpose.

But when it comes to the environment, the term invader (or invasive) is misleading. Animal and plant invaders aren’t willfully charging into new environments to conquer them.

In addition to being hazardous to young trees, rabbits can also cause other problems (see Plant a Tree-Sunbreak Press)

Photo by Cherie Ude

The first step in understanding invasive species is to define what an invader is. With stomping boots, flailing swords, and booming canons, it’s fairly to define and denounce the aggressive behavior.

But what transforms a warm and fuzzy bunny into an invader? (See National Geographic for the history of rabbits in Australia).

How does a species become an invader, destroyer of habitat, and a danger to human health?

Definition of Invaders

Defining an invasive species has proven controversial (Smithsonian Magazine). For the purposes of conservation, the definition from The International Union for Conservation of Nature, (IUCN) given in the Smithsonian Magazine article is commonly accepted:

“…animals, plants or other organisms introduced by man (emphasis my own) into places out of their natural range of distribution, where they become established and disperse, generating a negative impact on the local ecosystem and species.”

Clip Art Library Invasive Species Cartoon #2307916

In other words, humans not only identify and define the problem, they cause the problem.

Because of unthinking human behavior, defined invaders include animals and plants that we love and those we hate; those we brought with us on purpose and those who hitched rides on ships, planes, and even automobiles.

Because invaders enter new territory, they either quickly perish (wrong conditions) or thrive (no predators and more aggressive). Because of these factors (Invasive Species Specialist Group), invaders often eliminate natives and consequently alter entire ecosystems.

“Invasive alien species (IAS) are one of the five most important drivers affecting nature, and the fourth most important direct driver of species extinctions (Butchart et al. 2019; Ichii et al. 2019).” (PMC)

In other words, by creating this problem, humans are the cause of Invasive species that destroy habitat, damage ecosystems, and drive extinction. Since humans are the initial cause of the problem, humans must provide solutions. First, we must understand the problem.

Illegal Wildlife Trade–Many Victims

The illegal wildlife trade is responsible for many invaders. Animals are captured, transported, sold, and often die because someone wants the prestige of an exotic pet. Unfortunately, few people are able to care for exotic pets. People try, for instance, to keep full-sized jaguars in the city.

Even those who are supposedly professional find that providing fresh meat, ample space, and vet care exceed what they can provide (U.S. Department of Justice).

When care becomes too difficult or just boring, people “free” animals into the wild. Some don’t last long, but some find an Eden with no known predators, such as Burmese pythons and other exotic animals in Florida’s swamps National Geographic article.

Defying laws, people often think they have a “right” to own or consume any animal they want. However, wildlife trafficking is not a victimless crime. Consider this information from the 2022 US budget:

Law Enforcement—The 2022 budget provides $95.0 million, an increase of $8.1 million over the 2021 level, for the law enforcement program to investigate wildlife crimes and enforce the laws that govern the Nation’s wildlife trade. FWS continues to work with the State Department, other Federal agencies, and foreign governments to address the serious and urgent threat to conservation and global security posed by illegal wildlife trade and trafficking. A program increase of $7.7 million will provide for proactive law enforcement efforts to target and stop illegal trade; ensure sustainable legal trade through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; reduce demand for illegal wildlife products in consumer countries; and provide technical assistance and grants to other nations to build local enforcement capabilities. FWS will also continue to strengthen its smuggling interdiction efforts at the Nation’s ports of entry by using trained wildlife detector dogs in its frontline force and working with the State Department to support attachés in key wildlife trafficking countries in Asia, Africa, and South America. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

So the burden of policing and cleaning up after wildlife trafficking is placed on taxpayers. The same is true in other countries trying to prevent this crime. Citizens in these countries also suffer as animals go extinct and habitats are lost. Humans risk their health as well (World Wildlife Fund and above BBC article). Meanwhile, animals, too, endure capture, injury, and death.

Although many species come from other countries, we can’t simply blame other cultures for illegal wildlife trafficking. No one would capture the animals unless the market existed. For instance, social media has helped make the pangolin one of the world’s most trafficked animals – and not just because it’s cute. People unabashedly buy products made of their scales. World Wildlife Fund Is this a non-issue in the U.S.? No. This Portland, Oregon woman was selling the scales in the US U.S. Department of Justice.

The US is one of the largest consumers of illegal wildlife and products (One Green Planet: America’s Role in the Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Trade and How to Stop It).

The cute and cuddly aren’t the only deliberately purchased wildlife. Consider the lionfish, originally from the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, are now found in Florida coral reefs (NOAA ). People buy and then release these and other tropical fish in the sea. Now bounties are being offered to divers for killing lionfish (who have no local predators) before reefs are devastated. Again, the clean-up is costly and the environmental destruction extensive.

Kudzu sculpting a different forest landscape. (Photo by Kerry Britton, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org)

With plants, people who think something is pretty or interesting can create a serious environmental problem. Kudzu is swallowing up some landscapes.

At the same time the Himalayan blackberry offers a tasty treat, it can also overwhelm native plants (and even houses).

In some cases, the plants that take over an area can be hazardous to livestock and humans, such as tansy ragwort. Tansy (WSSA World of Weeds ) has been in the States for hundreds of years, and is considered noxious everywhere. It probably came over on ships accidentally, in ballast or agricultural products.

Invader Laws Vary

Every location that has had humans also has invasive species, both plant and animal. Each place has different rules and laws for invasive species management. For instance, the eastern grey squirrel is considered a “non-native” species in Washington State where I live. It’s legal to kill them, but illegal to move them off your property. Debate continues about how seriously they threaten native wildlife.

On the other hand, the European green crab (brought to the country aboard sailing ships) is a serious threat, and people are encouraged to report sightings. Check out National Invasive Species Information Center for specific information for your area. If you violate wildlife laws, you become subject to prosecution according to your state’s laws.

What Can You Do?

Be part of the solution.

- Read all labels when you purchase items, from clothing to furniture to toys to food. What are the materials and where do they originate?

- Buy certified products (US EPA Identify Greener Products and Services)

- Don’t buy exotic pets. If you want a pet such as a parrot, check out rescue centers. Many exotic pets need homes. Understand the animal’s needs before obtaining it.

- Don’t support markets or pet stores that sell any products that aren’t certified.

- Report any illegal wildlife trade. Share information about the problem with friends and family.

- Eco-tourism choices will help support local environmentally friendly economies.

- Support charitable organizations that fight wildlife trafficking. Check out World Wildlife Fund to start.

- Be informed. Do some research. Then be ready to speak out in person, on social media, or in letters to newspapers or congress about the problems and solutions.

Be part of the solution!

Next post will be on WATER in early April